Peace Education in the Primary Classroom

By Lisa Strykowski, Primary Guide

Thursday, September 18, 2025

“Peace is not just the absence of conflict;

peace is the creation of an environment where all can flourish.”

- Nelson Mandela

As we prepare to celebrate International Day of Peace this month, I’d like to welcome you to take a peek inside the Primary classroom to see how “Education for Peace” begins in the Children’s House.

We Begin with Self-Regulation

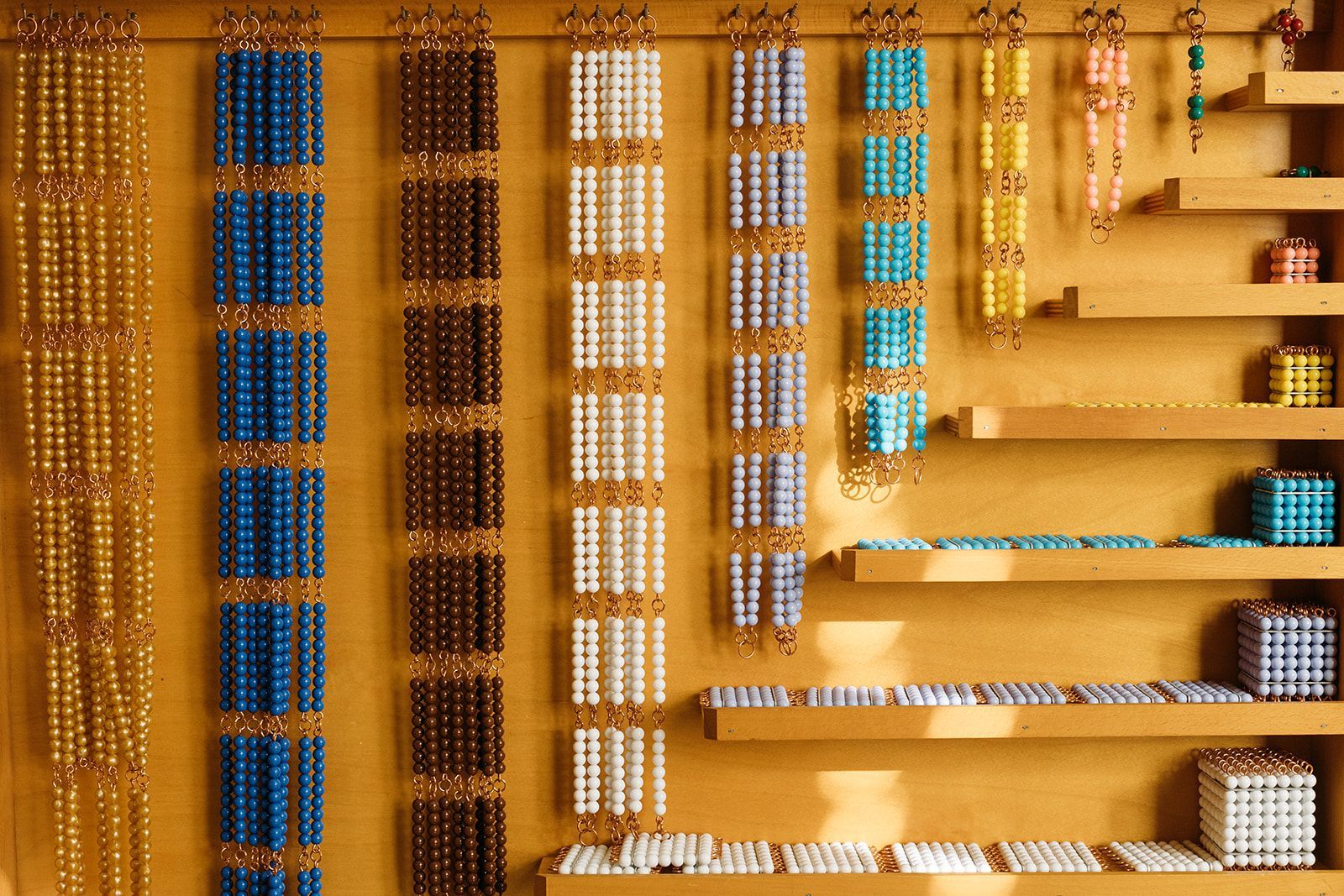

As the Primary child is discovering their sense of self, their will, and their relationship to others around them, we begin with exercises in self-regulation. In our classroom, these works are located on the Botany shelves, because “Peace is something we grow within us”. We have a small wooden finger labyrinth on a tray, which children learn how to trace inwards and outwards, taking slow, deliberate breaths. There is a small sand garden tray with a miniature rake and a few small rocks in a bowl. There is an assortment of life-size photographs of children’s faces on cards, displaying varying emotions, and a pedestal mirror, for practicing imagining what another person is feeling.

Growing Peace Within Us

One practice we do during morning circle to help grow peace within ourselves is to sit quietly in our criss-cross position with our eyes closed. We imagine peace as a small glowing ball of light inside each of us. It might be in our heads, or our hearts, or our bellies. It might just be a ball of colored light (like gold or pink), or it might be a picture. Some children have said they imagine peace looking like a stack of pancakes or like their Mommy’s face. Together, we take ten slow, deep breaths. With each breath, we imagine that we are feeding our peace and making it grow a little bigger and brighter.

Peace and Conflict Resolution

When two children in the Primary classroom are in conflict, we invite them to have a “Peace Conversation”. The person initiating the Peace Conversation would go get the Peace Rose (a white silk rose in a vase set aside by itself in the classroom) and bring it to the person they want to have a Peace Conversation with. The rule in our classroom is that if you are asked to have a Peace Conversation, you may ask for five minutes to calm down or finish your work first, but you may not refuse the conversation. A teacher will remain close by to observe and facilitate if needed.

The Peace Conversation process is based on Marshall Rosenberg’s Nonviolent Communication and follows four basic steps: 1) a nonjudgemental observation, or “When this happened…”; 2) an expression of feelings, or “I statement”; 3) connecting those feelings to needs; and 4) making a specific request of the other person.

An example of this might be:

“Bobby, when you asked Peter to sit with you for lunch, it hurt my feelings because yesterday you promised me you would sit with me for lunch today. It makes me feel like you’re not my friend. I need you to keep your promises. Can we move to a bigger table where we can all sit together?”

The first child then hands the Peace Rose to their friend. Often, the child will immediately apologize, but other times they will not know what to say. In this case, the teacher may ask the second child, “Would you like to ask your friend ‘What can I do to make things right with you?’ Maybe they would like to hear I’m sorry, or maybe they would like a hug, or maybe they just want to hear that you won’t do it again.” Asking this question in Primary frequently results in a request for a hug, which is quickly given.

Speaking at the International Montessori Congress in 1937, Maria Montessori said, "If we are among the men of good will who yearn for peace, we must lay the foundation for peace ourselves, by working for the social world of the child."