My Parent Teacher Conference Journey

By Rob Lewicki, Upper Elementary Guide

Thursday, October 23, 2025

I’ve been a teacher longer than I’ve been a parent. Each role has shaped the other—especially after I became a Montessori teacher. Parenting provides greater perspective for my conferences and tough conversations; teaching provides useful tools and language for how I parent. By sharing a few personal stories, I want to make hard school conversations easier to process and to nudge families toward earlier action. I’ve heard it can take hearing something about a child from three sources before a parent acts; while that isn’t always true, I’ve watched it take even longer. My hope is that this reflection helps families recognize the important messages sooner and feel more prepared to respond.

My first DISD parent teacher conferences were at Esperanza ‘Hope’ Medrano Elementary. At my very first conference as a brand-new teacher, the father of one of my students asked me if I had children. I remember being slightly offended. Was Ana’s father implying I could not be a good teacher without having children? When I let him know I did not have children and then asked him why it mattered, he replied, “If you have children, you will know.”

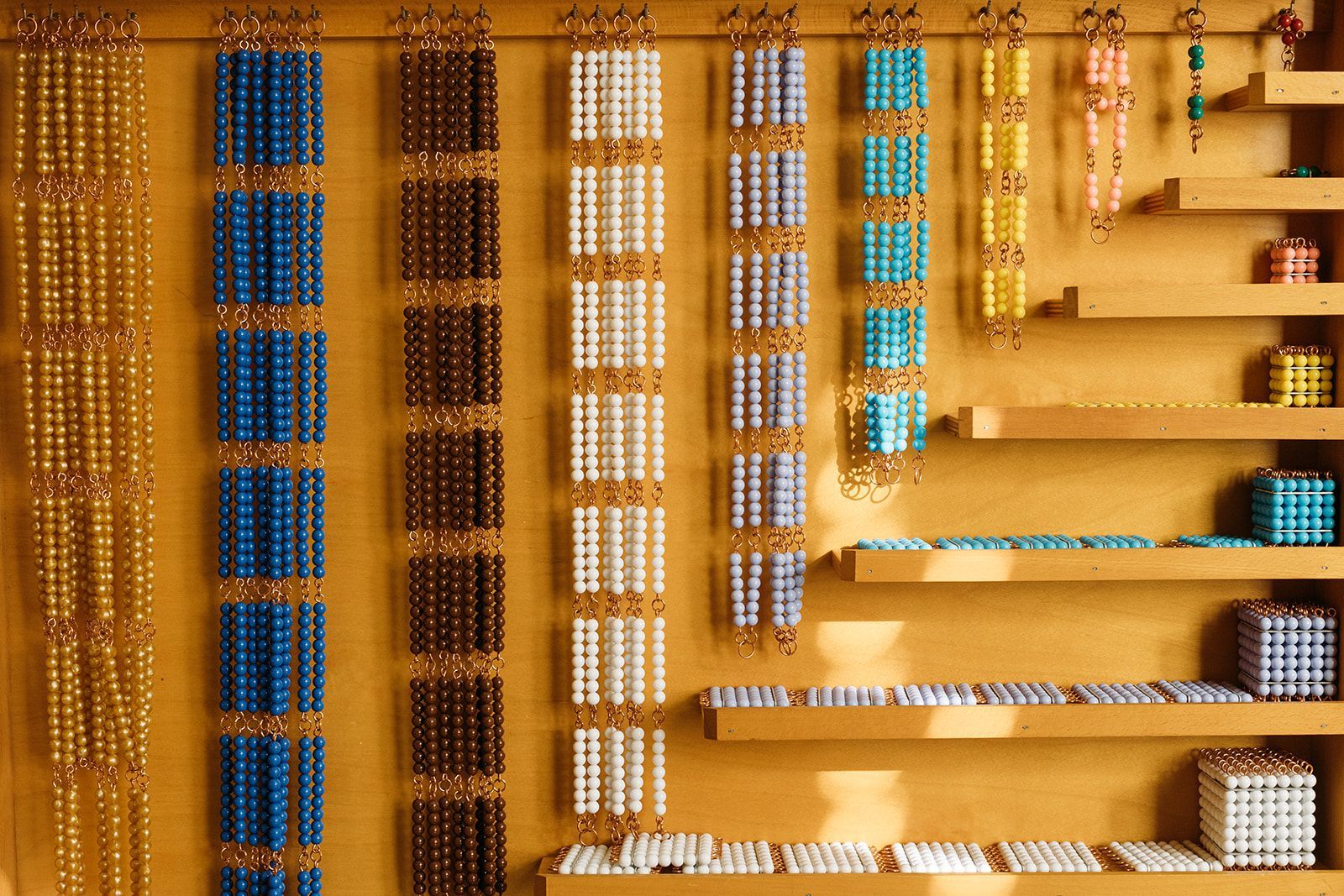

My first parent teacher conference as a parent was here at White Rock Montessori. My son Jack was a three-year-old in Primary 1. His teachers were Mrs. Akin and Mrs. Bolano. Mrs. Bolano, a woman I have often referred to as the Goddess of Education, was the teacher with whom I conferenced. I remember about ten minutes into the conference I had to stop Mrs. Bolano and tell her I hadn’t understood a lot of what she was saying. Everything she said sounded really nice, and it seemed like Jack was doing well, but it also sounded like he was having trouble with… pencils? Somehow?

Mrs. Bolano was very patient with me. She let me know that Jack needed to strengthen his hand so that he would be able to hold a pencil properly. Cutting strips of construction paper and coloring with crayons would be helpful. I thought, “Why didn’t she just say that to begin with?” I wondered.

The conference where I finally understood why Ana’s father had asked me if I had children, was at Lake Highlands Elementary. My son Benjamin was attending speech therapy there twice a week as a four-year-old. Benjamin didn’t speak until he was almost two and a half. It was through the Richardson School District and his teacher and program were wonderful. The speech therapists that evaluated Benjamin said that he was plenty smart, and they did not know why he wasn’t talking, only that he would. They recommended he attend this new class for preschool children that was starting up at the elementary school by the public library. So Ben went there for three years, sometimes leaving his Primary classroom at White Rock Montessori early so that he could attend the speech class. I could tell his teacher cared for Ben and he definitely liked his teacher. In his last year in the program, my wife and I were called in for a special conference and she told us she suspected that Benjamin was autistic. We agreed to have him tested by the district, and it turned out Benjamin is autistic.

This hit me hard. In the moment I knew I should be asking questions, gathering information, figuring out next steps, and learning how to help my child. Instead, I was irrationally angry. I had my arms crossed and was leaning back against my chair. The only thing I remember saying was, “Will he be able to go to college?” The clear path I had envisioned for my son to have a happy life - school, college, marriage - was no longer clear. It hurt and I was deeply worried. I think they recommended I read some books, but I can’t remember the conversation clearly. It didn’t go very well. It can be hard to be rational when you perceive your child to be in peril.

My first conferences as a Montessori teacher were at White Rock Montessori. I was a new Montessori teacher, but had been a parent for 6 years and had three children - 2 in Primary and one in Lower Elementary. During my first five years as a Primary teacher I had, what seemed to me, a large number of children with learning challenges. Many of my parent conferences became a series of conferences, where the parents of my students and I worked together, learned together, and problem solved to figure out how to best help their children. Though these years were really challenging, they were also incredibly beneficial because I learned so much about the learning differences and the needs of my various students.

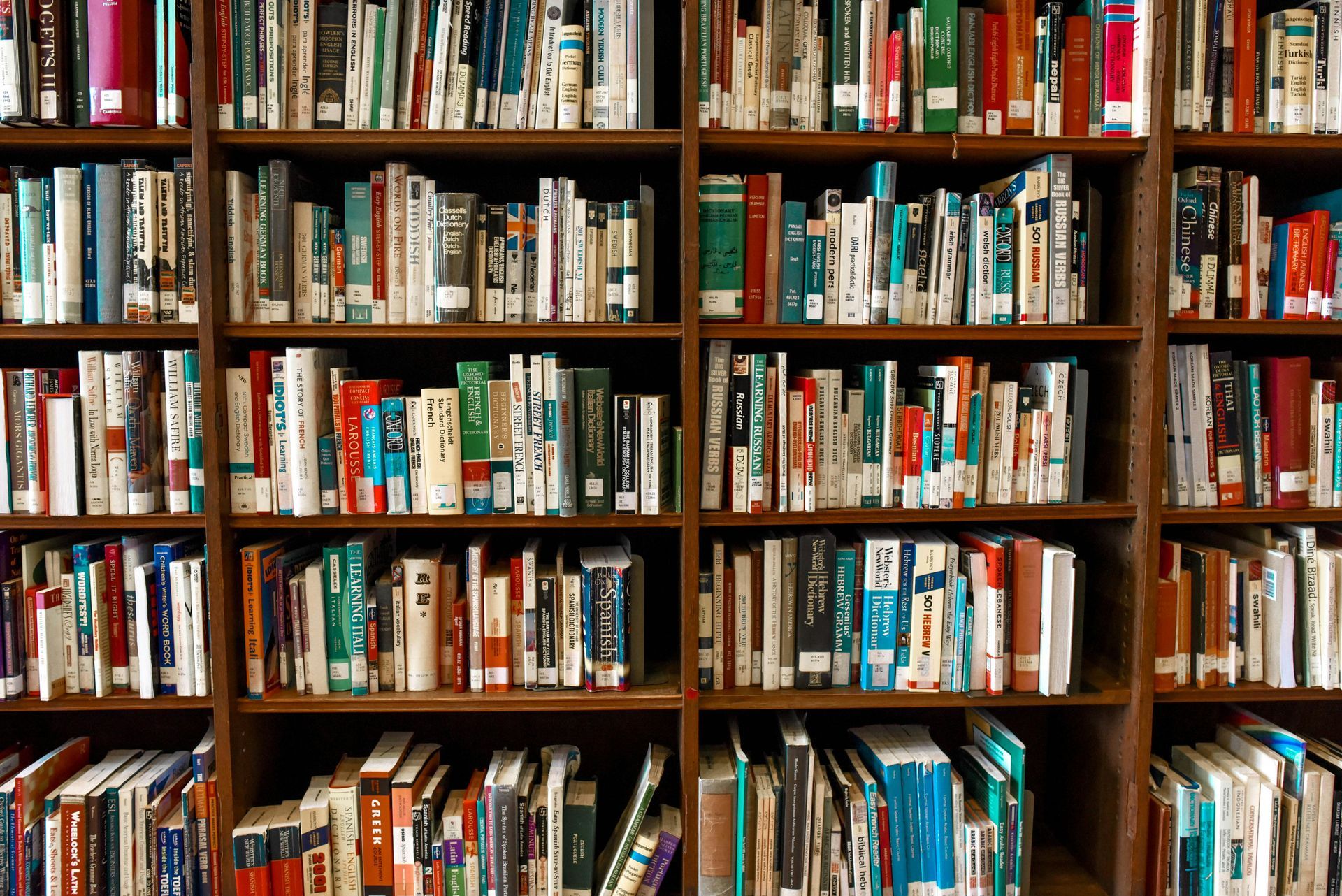

Two years into my Montessori teaching career, I had a parent teacher conference with my daughter’s Primary teacher. She was very concerned about my daughter’s reading ability - or rather lack of reading ability. My family is a family of readers. There are bookshelves full of books in our house. The idea that our child would not get to share in this “reading world” with us hit pretty hard. However, this was not my first rodeo.

I did ask a lot of questions and talked to our reading specialist. She did a quick test and let us know that our daughter more than likely had dyslexia. We went through Scottish Rite to get her a full evaluation, but they had quite a backlog, and she wouldn’t be seen for 6 months. Something I had learned as a teacher is that we didn’t need to wait for an evaluation to start helping a child. We got her into tutoring, attended some dyslexia ‘camps’ that were more about building self-esteem than reading skills, and just read with her every night. I had learned that the world would not end if I had a child with a learning difference.

I have had many many more parent teacher conferences as a teacher at White Rock Montessori. Most are easy. Some have been very hard. I have had parents sitting with arms crossed, obviously upset. I have had parents share insights that helped me understand their child. I have had parents who knew what they needed to do to help their child, but always had a reason why they couldn’t. And I have had parents that did research, tried out all sorts of strategies at home, and then helped me incorporate what they had learned into our classroom. Sometimes parents are just not ready to hear what I'm trying to tell them about their child. I say it anyway, hoping that they will be ready to hear it when the next teacher tells them.

I know that being a parent made me a better teacher. I know that being a Primary teacher made me a better parent to three young children. I know that having children with learning challenges has made me more empathetic with the parents who are discovering their children may learn differently for the first time or are trying to navigate the best way to help their children.

I used to dread parent teacher conferences when I first started teaching in public school and then again at the start of my time as a Montessori teacher. Now I look forward to them. So much good has come out of this time I get to spend talking with parents. A time where everyone at the table is focused on one child and we are all working together to find the best way to help that child. It can really be amazing.